Key Takeaways

This judgment provides three clear implications regarding the admissibility of expert evidence in crypto-asset related matters.

- Transparency is Mandatory: Courts will reject expert evidence if the cryptocurrency tracing methodology cannot be clearly explained or verified by the opposing party [J.55].

- “Black Box” Evidence is Fatal: An expert cannot rely on proprietary software or “investigative experience” as a substitute for a principled, reproducible method [J.60].

- Mathematical Rigour is Required: If the numbers do not add up during a judicial “mathematical audit,” the evidence will be dismissed as unreliable [J.67].

Case Citation & Jurisdiction

- Case Name: Fabrizio D’Aloia v Persons Unknown Category A and Others

- Neutral Citation: [2024] EWHC 2342 (Ch)

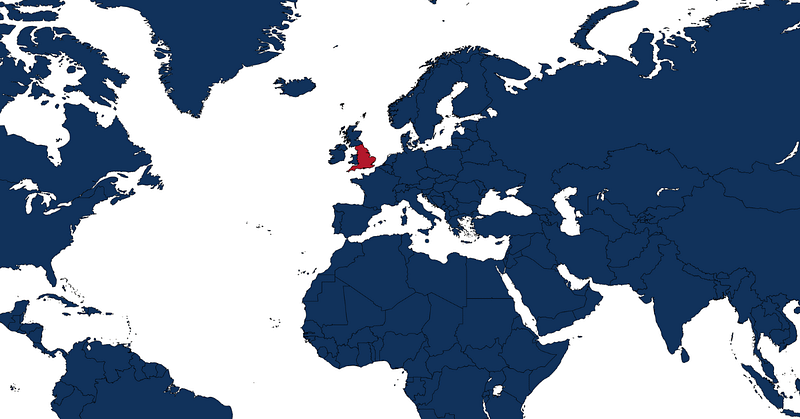

- Jurisdiction: High Court of Justice of England and Wales, Business List (Chancery Division)

- Date of Judgment: 12 September 2024

Factual Background: D’Aloia vs. Persons Unknown

The Claimant, Mr D’Aloia, was the victim of a sophisticated cryptocurrency investment scam that began in July 2021. He was duped into believing he was investing through a legitimate cryptocurrency exchange. This conviction led to the transfer of a substantial quantity of digital assets.

In total, approximately 2.1 million USDT, a stablecoin, was stolen across multiple transactions. The core of the legal action focused on one specific tranche of 400,000 USDT.

The fraudulent transactions were traced to a specific wallet address controlled by the anonymous fraudsters (Persons Unknown). The central factual issue was the subsequent movement of those specific funds.

The Claimant asserted that the 400,000 USDT were moved through the blockchain and ultimately reached an account held at the Sixth Defendant, Bitkub. Bitkub is a registered VASP (Virtual Asset Service Provider) based in Thailand. The entire case against Bitkub hinged on establishing this final link via cryptocurrency tracing evidence.

Can a “Black Box” Tracing Methodology Support a Claim?

The central evidentiary challenge was whether an expert’s tracing methodology could be relied upon when it lacked transparency and consistency.

The Claimant’s expert purportedly applied a First-In-First-Out (FIFO) methodology to trace funds from the point of loss to Bitkub’s wallet address. However, he admitted in cross-examination that he had “refined” this approach based on proprietary software training [J.245].

This created a “black box” scenario. The court was asked to trust the expert’s findings without being able to independently verify the flow of funds [J.259].

Key Findings

The Rejection of the Expert Evidence

The Court found the expert’s evidence to be “chaotic and, ultimately, contradictory” [J.58]. While the expert claimed to use FIFO, the court found he had applied a subjective methodology that cherry-picked transactions to maximise the Claimant’s recovery [J.262].

Crucially, this methodology ignored the funds of other potential innocent victims. By disregarding pre-existing balances and intermediate incoming funds, the expert violated the principle of treating innocent contributors equally [J.262].

The Necessity of a Transparent Methodology

The court emphasised that while English law permits tracing methods beyond strict FIFO (such as pari passu or rolling charge), any alternative must be “methodologically sound and properly evidenced” [J.7iii].

In this instance, the lack of a coherent, explainable method meant the court could not perform a mathematical audit of the flow of funds [J.67].

Consequently, the court held that the Claimant had failed to prove, on the balance of probabilities, that any of his funds reached the Defendant’s wallet [J.264].

Analysis & Implications

Litigators cannot rely on an expert’s credentials or the reputation of their proprietary software alone. Defensibility requires transparency. Experts must be able to open the “black box” and explain, step-by-step, how the software reached its conclusion.

If the methodology cannot be replicated or mathematically audited by the court, the evidence risks being ruled inadmissible. When instructing a blockchain expert, insistence on a defensible methodology is critical, rather than accepting a simple software printout.

Experts must be capable of explaining their logic to a layperson, and their chosen method of accounting for commingled cryptocurrencies (whether FIFO, pari passu or otherwise) should be applied consistently, rather than conveniently.