Key Takeaways

- USDT attracted Property Rights: The High Court confirmed that stablecoins can constitute a distinct form of property under English law, satisfying the Ainsworth criteria.

- Constructive Trusts Apply: The court accepted that a constructive trust potentially arises over crypto assets obtained by fraud.

- Opaque Evidence Can Be Fatal: The claim failed because the cryptocurrency expert’s methodology could not be verified or explained step-by-step.

- Transparency is Crucial: This judgment suggests that courts will rigorously scrutinise forensic reports to ensure they allow for a “mathematical audit” of the flow of funds, particularl;y where commingled funds exist.

Case Citation & Jurisdiction

- Case Name: Fabrizio D’Aloia v Persons Unknown Category A and Others

- Neutral Citation: [2024] EWHC 2342 (Ch)

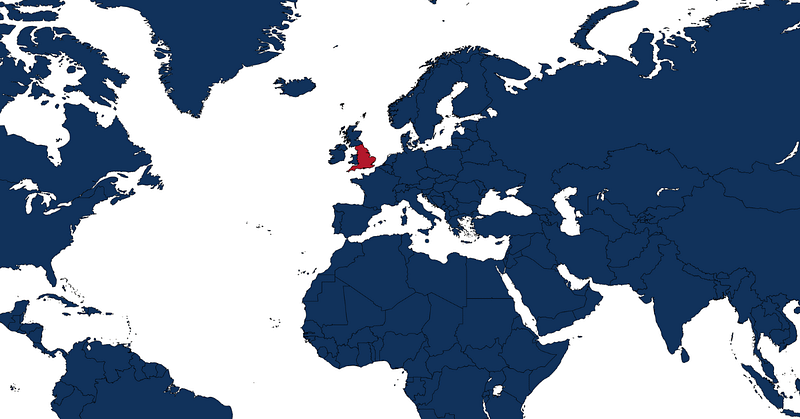

- Jurisdiction: High Court of Justice of England and Wales, Business List (Chancery Division)

- Date of Judgment: 12 September 2024

Factual Background

The Claimant, Mr D’Aloia, was the victim of a sophisticated cryptocurrency investment scam involving a platform known as “td-finan”. He was duped into believing he was investing through a legitimate cryptocurrency exchange, leading to the theft of approximately 2.1 million USDT.

The legal action against the Sixth Defendant, Bitkub, focused on one specific tranche of 400,000 USDT. The Claimant asserted that these funds were traced through the blockchain to a wallet hosted by the Thai-based exchange.

Bitkub defended the claim on the basis that they never received the Claimant’s specific crypto assets. Consequently, the case turned on the reliability of the tracing evidence used to link the theft to the exchange. [J. 1-2]

Can Legal Liability Exist Without Transparent Tracing Evidence?

The central challenge in D’Aloia was whether established legal principles could succeed when the underlying forensic evidence was opaque. The Claimant successfully argued the theoretical points regarding property and trusts. However, the claim failed because the expert’s methodology could not be verified to prove the USDT in question reached the defendant.

The High Court’s Findings

Issue 1: Is USDT Property under English Law?

The court addressed the foundational question of whether stablecoins attract property rights [J.106]. It ruled that USDT is a distinct form of property under English law, satisfying the classic Ainsworth criteria. This finding rejected the argument that crypto-assets are merely information incapable of being owned.

We examine the full implications of this property ruling in our detailed breakdown: Is USDT Property Under English Law?

Issue 2: Constructive Trusts and VASPs

The judgment confirmed that a constructive trust may arise over assets obtained by fraud [J. 19-21]. However, the claim against the exchange failed on the facts because the VASP was not found to be shown to hold any trust funds. Without proven receipt, the exchange could not be liable as a constructive trustee.

We analyse the court’s refusal to impose a trust on the exchange in our focused article: Constructive Trust Claims Against Cryptocurrency Exchanges.

Issue 3: The Flaw in Tracing Methodology

The dismissal of the claim hinged on the rejection of the claimant’s expert evidence. The court found the expert’s methodology to be “chaotic” and contradictory, lacking a transparent, replicable method [J. 58]. This failure to verify the flow of funds meant the necessary legal link to the defendant was missing.

We detail the specific methodological errors that proved fatal to the claim in our expert review: Cryptocurrency Tracing Methodology Scrutinised.

Analysis & Strategic Implications: A Forensic Case Study

While D’Aloia is a UK High Court decision and not binding in other jurisdictions, it illuminates a challenge relevant to litigators globally. The judgment offers an insight to how courts may approach the gap between legal theory and forensic evidence. It highlights that establishing property rights is effective only if the underlying tracing data is accepted by the court.

Litigators may find the court’s focus on the “verifiable audit trail” of the tracing report particularly noteworthy. The case illustrates that defendants can successfully challenge claims by scrutinising the expert’s ability to explain their methodology. This suggests that defensibility often hinges on a clear, replicable explanation of fund movements.

Ultimately, while specific to English law, the ruling typifies a broader tension between automated tools and forensic rigour. An expert witness was required to articulate their logic clearly, rather than relying solely on software outputs. This focus on transparency provides a useful reference point for future cross-jurisdictional disputes.