Key Takeaways

- USDT is Property: The UK High Court ruled that the stablecoin USDT is subject to property rights under the law of England and Wales.

- A Distinct Form of Property: The court found that USDT is neither a ‘chose in action’ nor a ‘chose in possession’ but is instead a distinct, third category of property.

- Satisfies the Ainsworth Criteria: USDT was found to meet the classic four-point legal test for property, as it is definable, identifiable, capable of assumption by third parties, and possesses some degree of permanence.

- Enables Proprietary Claims: This ruling confirms that USDT is capable of being the subject of tracing and can constitute trust property, reinforcing the availability of equitable remedies for recovery.

- Technology Merits Considered: The judgment indicated that while all cryptocurrencies are not the same, the court will analyse the specific technology and its function to determine its legal status.

Case Citation & Jurisdiction

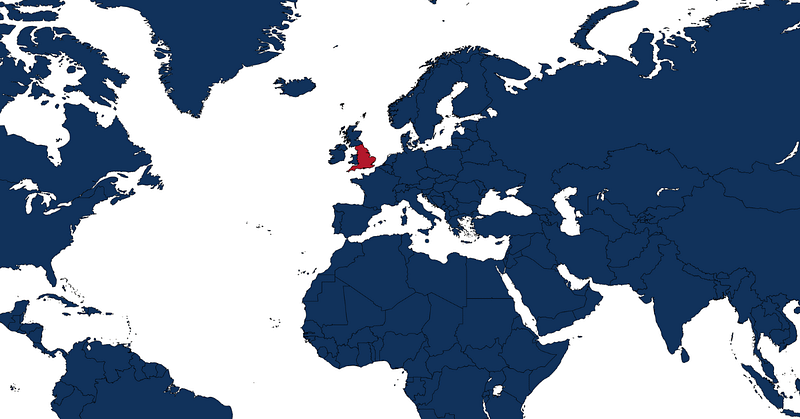

- Case Name: Fabrizio D’Aloia v Persons Unknown Category A and Others

- Neutral Citation: [2024] EWHC 2342 (Ch)

- Jurisdiction: High Court of Justice of England and Wales, Business List (Chancery Division)

- Date of Judgment: 12 September 2024

Factual Background

The Claimant, Mr D’Aloia, was the victim of a sophisticated cryptocurrency investment scam that began in July 2021. He was duped into believing he was investing through a legitimate cryptocurrency exchange. This conviction led to the transfer of a substantial quantity of digital assets.

In total, approximately 2.1 million USDT was stolen across multiple transactions. The fraudulent transactions were traced to a specific wallet address controlled by the anonymous fraudsters (Persons Unknown). [J. 2]

The case against the anonymous fraudsters and the Virtual Asset Service Providers (VASPs) that subsequently received the assets hinged on several complex legal and technical questions. To pursue proprietary remedies, such as a constructive trust—which relies on the process of tracing—a foundational question had to be answered: Were the stolen assets legally considered “property” at all? [J. 5]

Are Stablecoins Legally Recognised as Property?

For the Claimant to pursue any proprietary claim, the court first had to determine if the stolen assets—USDT—could be legally defined as property under English law.

While both the Claimant and Bitkub (the Defendant) accepted that USDT is something to which property rights can attach [J. 105], the court still conducted a detailed analysis. Bitkub’s own business model as an exchange is premised on such assets having legal recognition. [J. 5]

The court’s detailed analysis was necessary to address strong, opposing arguments from academic commentary—namely, that crypto-assets are “mere information” and that property must be tied to legally recognised rights.

To provide a solid basis for its finding, the court had to counter this “information argument”. It did so by defining the asset not as mere data, but as a “composite thing” combining data with “transactional functionalities”. This combination, the court found, is sufficient to attract property rights. [J. 156 – 166]

The High Court’s Findings: Applying the Ainsworth Criteria to USDT

The High Court’s final determination was that USD Tether (USDT) unequivocally attracts property rights under English law.

The court’s analysis was methodical. It drew heavily on the principles applied to Bitcoin in AA v Persons Unknown, which utilised the four classic criteria for property set out in National Provincial Bank v Ainsworth.

The High Court found that USDT satisfies all four Ainsworth criteria:

- It is definable: USDT can be clearly defined by reference to its data structure, the public ledger, and its cryptographic security.

- It is identifiable by third parties: The existence of a specific USDT token is verifiable by third parties through the public blockchain.

- It is capable of assumption by third parties: The nature of the blockchain system is that third parties can assume the power to control and transfer the asset.

- It has some degree of permanence or stability: The asset’s persistence is secured by the distributed ledger.

The court concluded that USDT is a distinct form of property, separate from a ‘chose in action’ or ‘chose in possession’. [J. 108 – 134]

Rejecting the “Mere Information” Argument

A significant hurdle addressed by the court was the academic argument that crypto-assets are “simply information” and that English law generally does not recognise property rights in mere information.

The court countered this by defining the property as a “composite thing”. It found that the asset is not just the data (the public and private keys) but a combination of that data and its “transactional functionalities”. This combination gives the asset a form and expectation of performance sufficient to attract property rights. [J. 156]

The “Extinction/Creation Argument” vs. The “Persistent Thing”

The court also analysed the “extinction/creation argument”—a technical position that upon transfer, the existing USDT token is “destroyed” and a new one is “created”.

This technical distinction is legally critical. If an asset is “destroyed” on transfer, it becomes impossible to “follow” it to a new owner; one could only “trace” its value.

The court rejected this analysis, characterising USDT as a “persistent thing”. It was found that the core property—the combination of data and transactional functionalities—remains unchanged upon transfer. This persistent identity makes it more like a chose in possession, and the court accepted that, in principle, “following” the asset should be an option. [J. 204]

Analysis & Implications

This judgement is a clear signal that the High Court focused on the function of a crypto-asset, not just its underlying technology. The court acknowledged the technical differences between assets but ultimately regarded their function as similar enough to be treated the same for the purposes of the law.

For litigators, this judgment provides a solid, trial-level precedent based in the UK that stablecoins like USDT are property. This finding strengthens the foundation for proprietary remedies.

However, the ruling also serves as a warning. While the court found in favour of this asset, its willingness to dissect technical arguments (like “extinction/creation”) shows that the specific merits of an asset’s technology are now firmly in play.

Litigators should be aware that all crypto-assets are not the same. This precedent may not apply uniformly to a different token with a different technical architecture. The defensibility of a future claim may hinge on an expert’s ability to explain why a specific asset meets the Ainsworth criteria, just as was done in D’Aloia.